This article is specifically tailored to the context, needs, and legal obligations of Dutch public-sector organizations. However, most content is relevant to other organizations in and outside the Netherlands.

Why AI Procurement Is Becoming the New Focal Point of Government Digitalisation

Over the past five years, government organisations have made significant progress in their use of AI. While in 2019 most applications focused on image recognition for supervision, inspection, maintenance, and mobility, recent research shows that the scope of AI has expanded considerably. By 2024, archiving, anonymisation, document processing, policy analysis, and text-based AI have become some of the most important use cases. Generative AI was hardly on the government’s radar a few years ago, yet it is now rapidly evolving into a core technology for virtually all document flows.

At the same time, the Dutch Court of Audit (“Algemene rekenkamer”) highlighted an important reality in 2024: the majority of public-sector organisations use AI without clearly understanding the associated risks or how algorithms are documented and registered. Governance efforts in recent years have mainly focused on ethics, policy frameworks, and programme-level steering. But one crucial domain is lagging behind: AI increasingly enters organisations through the procurement chain, often without clarity on what functionality is enabled, which data are used, or what risks are introduced. This is even more pronounced because AI systems are no longer developed exclusively in-house.

It is also important to note that contract management plays a key role—yet it is often the most overlooked element in the procurement lifecycle. In practice, attention is typically high during the tendering process but fades once the contract is signed.

This makes AI procurement the new centre of gravity in government digitalisation. More and more vendors are adding automatic AI components to existing software, often through routine updates. A system originally designed for simple data processing may quietly transform into a machine-learning application. Public organisations remain legally responsible for compliance and quality, even when the AI component was not explicitly purchased.

Two developments further increase the urgency. First, the arrival of the AI Act, which imposes obligations on both providers and users. Public bodies must additionally meet existing legal duties: the GDPR, the General Administrative Law Act, the Archives Act, the Open Government Act, and human-rights obligations relating to non-discrimination and proportionality. In the public sector, any AI failure is immediately placed under intense scrutiny.

Second, the pressure on public services continues to rise. While AI is deployed to support societal challenges, AI use by citizens and companies simultaneously increases the volume of appeals, subsidy applications, information requests, and complaints. As a result, the effectiveness and ROI of AI systems have become more critical than ever.

It is increasingly clear that control over AI does not begin with the technology itself, but with the way AI enters the organisation and becomes embedded in everyday processes. The procurement chain—including contract management—has become the point where most risks arise, yet it remains the least mature element of AI governance.

Where AI Risks Truly Emerge—and Why Organisations Still Miss Them

AI-related risks are no longer limited to specific projects or algorithms developed by internal data-science teams. AI is now embedded in standard software packages, cloud platforms, search tools, document-analysis functions, and dashboards. The AI Act does not distinguish between bespoke or procured AI systems. The central question is simply: Does this system contain an AI model—yes or no?

In practice, many organisations cannot answer that question with certainty. One major reason is the speed at which vendors introduce new AI components into existing functionality. Where document classification, predictive analytics, or cleaning algorithms once relied purely on rules or simple statistics, vendors are now rapidly adding AI modules built on machine learning or generative techniques. These modules often arrive as “feature enhancements,” without customers consciously opting into AI. The transition happens quietly through updates, leaving organisational decision-making lagging behind the actual technology.

Public organisations are legally required to identify, classify, and manage risks. This means assessing not only compliance with the AI Act, but also internal risk factors—such as the likelihood of bias, incomplete or inaccurate input data, declining model performance, reduced explainability, or contextual changes that weaken model reliability. AI is not a static product; it is dynamic, context-dependent, and requires ongoing quality assurance.

Meanwhile, responsibilities within government are complex. Programme and project owners typically initiate early conversations with vendors and research partners. Technical specialists manage data quality, logging, and monitoring. Executives and managers are accountable for legality, public values, and societal legitimacy. Procurement teams lead the tender process and set contractual requirements. If any of these links is insufficiently structured, a governance gap emerges. Today, that gap is most visible in procurement and contract management.

How Public Bodies Can Already Regain Control of AI Through Procurement

Many of the tools needed to responsibly procure AI already exist. The challenge is not a lack of frameworks, but rather the consistent application of those frameworks within standard procurement and contract processes.

A key foundation is the PIANOo AI procurement conditions. Developed by the City of Amsterdam and now recommended by the European Commission as a leading practice, these conditions provide concrete guidance for procuring AI responsibly. They define requirements for both low- and high-risk AI and cover documentation, data-quality safeguards, logging, and audit and inspection rights for vendors.

Increasingly, structural transparency and documentation are essential. This begins with clear information about the data used to train models, design choices, algorithms, and performance indicators. Logging and version control provide insight into model behaviour and the frequency of updates. Bias analyses, evaluation reports, and verification documentation enable organisations to prove that a model operates within legal and ethical boundaries.

A powerful internal tool is the creation of a model registry, actively linked to the algorithm register many public organisations already maintain. The algorithm register provides public transparency; the model registry offers the technical depth required for quality assurance. The maturity of these registers is accelerating due to new software solutions that help monitor AI at scale. Local players such as Deeploy offer tooling to systematically manage model behaviour, drift patterns, data quality, and monitoring. International solutions like IBM WatsonX.governance provide enterprise-grade support for documentation, compliance, workflow control, and explainability. By establishing a solid internal model registry and leveraging these technologies, organisations can gain a complete view of AI risks across the entire system lifecycle.

When assessing vendors, it is critical to require verifiable evidence. ISO 42001, the new AI governance standard, provides a robust basis for this. Vendors that demonstrably comply with this standard show that they have embedded risk management and quality control throughout their organisation. For public procurers, including ISO 42001 conformity in tenders is a “no-brainer”: it makes vendor selection more objective, robust, and transparent. The standard directly aligns with the obligations of the AI Act and addresses the full governance lifecycle of AI.

An increasing number of public organisations also choose to commission independent validation of procured AI systems. Nemko AI Trust is one such instrument. It provides an objective evaluation of whether an AI system meets required quality, risk-mitigation, and transparency criteria. Applying such validation is remarkably easy and comes at no cost to the public organisation; the vendor typically pays for the assessment. This makes external verification a low-barrier approach to establishing assurance in domains where risks are highest.

Contract management is the final component of responsible AI procurement. The question is whether the AI system continues to meet the requirements set out in the contract, and how it is embedded within existing operational processes. AI systems change during the contract period: vendors add new models, modify data processing, adjust algorithms, or introduce generative functions. Without active monitoring, these changes remain invisible. Contract management must therefore evolve to include the capability to evaluate AI performance, identify and assess technical changes, and escalate issues when needed. This requires close collaboration between technical teams, policy advisors, and procurement and forms an integral part of modern AI governance.

At its core, responsible AI procurement means assessing not only what is being purchased today, but also how the system will evolve during its use. That is the foundation of sustainable control.

A Pragmatic Policy Framework for AI Procurement

Government bodies have developed many guidelines and principles for AI, but these are not always concrete enough for direct use in tenders and contracts. A policy framework is therefore needed that is legally complete yet practical enough to apply within day-to-day procurement, IT management, and operational processes. The framework below provides exactly that: it translates high-level principles into actionable decision points for any procurement process involving AI.

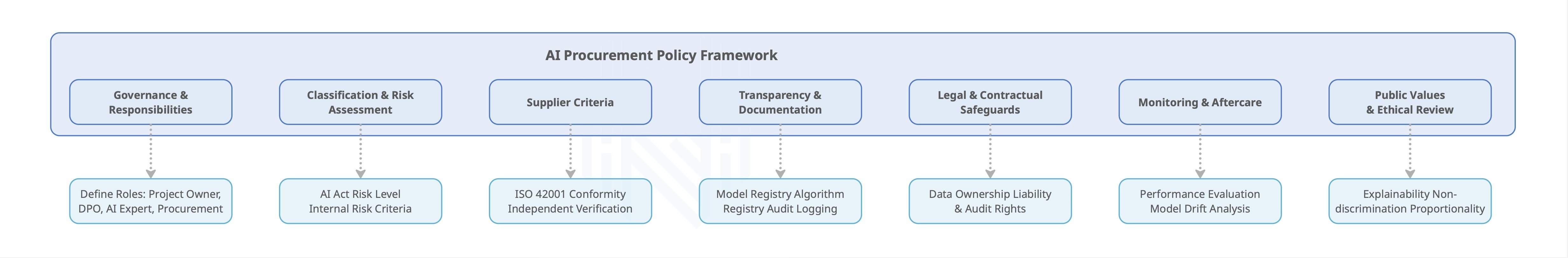

Figure 1: The seven domains of the AI Procurement Policy Framework

It is designed for rapid use and ensures that all relevant disciplines—executive leadership, policy, technical teams, procurement, and contract management—work from the same playbook. This enables a coherent approach that supports not only the procurement phase but the full lifecycle of the AI system.

| Domain |

Policy Question |

Concrete Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Governance & Responsibilities | Who is accountable for the purpose, risks, and assurance of AI within the procurement and throughout implementation? | Define roles such as sponsor, project lead, data-protection officer, AI expert, procurement officer, and contract manager. Include these in tender and project documentation. |

| Classification & Risk Assessment | Does the system fall under the AI Act, and what is its risk level? What internal risks are relevant? | Conduct a risk assessment based on the AI Act, Annex III, and internal criteria for data quality, explainability, and impact. Engage independent experts where needed. |

| Vendor Requirements | What requirements apply to vendors, and how is compliance demonstrated? | Request evidence of conformity with ISO 42001 and ISO 23894. Require documentation on data, models, bias assessments, and security. Consider independent verification such as Nemko AI Trust. |

| Transparency, Documentation & Data Quality | How will the system remain explainable, traceable, and controllable? | Require datasheets, model documentation, audit logs, version control, and quality reports. Ensure integration between the model registry and the algorithm register. |

| Legal & Contractual Safeguards | How are responsibilities and rights formalised? | Include AI-specific clauses on data ownership, liability, audit and inspection rights, update obligations, and cybersecurity. |

| Monitoring & Post-Implementation Assurance | How is reliability ensured after deployment? | Define requirements for periodic performance evaluations, incident management, drift analysis, and reassessment of risks. |

| Public Values & Ethical Review | How are societal values safeguarded during design and use? | Establish reviews focused on explainability, non-discrimination, proportionality, and the protection of human oversight. |

Conclusion – Real Control Over AI Begins in the Procurement Chain

The public sector has invested heavily in AI governance, but the point where AI actually enters the organisation remains the most vulnerable. The procurement chain is the main route through which new AI functionality is introduced—often without full visibility into risks or documentation. As a result, AI that is carefully governed elsewhere may still introduce significant risks once vendors deploy updates or activate new modules.

To maintain control over AI, organisations must start with procurement. This requires clear requirements for vendors, robust documentation, strong risk assessments, and the use of emerging verification instruments such as Nemko AI Trust. It requires tooling that enables monitoring at scale. And it requires an organisational mindset that recognises AI evolves during use and therefore demands continuous oversight.

With PIANOo conditions, ISO 42001 alignment, model and algorithm registers, modern monitoring software, and professional contract management, the public sector already has the foundation needed to deploy AI safely, transparently, and sustainably. This creates a strong basis for realising societal value through AI without compromising public responsibility.

The steps that public bodies can take now are clear:

- Identify which systems contain AI (a requirement of the AI Act).

- Assess the associated risks

- Set vendor requirements that mandate demonstrable quality.

- Establish a model registry linked to the algorithm register.

- Implement tooling to professionalise monitoring and governance.

- Elevate contract management into a full-fledged component of AI oversight and control.

- Use external validation at no cost to verify high-risk or critical systems.

Taken together, these steps form a mature and future-proof foundation for responsible AI deployment in the public sector.

AI Expert Authors

Marieke van Putten

Marieke van Putten, Business Consultant at Nipi Advies has extensive public-sector experience, consulting for many years before joining the Ministry of Economic Affairs to lead innovation programmes. From 2018–2022 she coordinated international digital-government affairs on AI and Blockchain, represented the ministry in EU AI groups, chaired the NL AI Coalition’s public-services group, and now works independently, giving masterclasses on innovation procurement, AI and ethics.

Bas Overtoom

Bas Overtoom is the Global Business Development Director where he leads global efforts to promote responsible AI adoption at Nemko Digital, working with organizations to operationalize trust, transparency, and compliance in their AI systems. With a strong background in business-IT transformation and AI governance, he brings a pragmatic approach to building AI readiness across sectors.